Microwave radiofrequencies, 5G, 6G, graphene nanomaterials: Technologies used in neurological warfare

Fabien Deruelle, Independent Researcher, Ronchin, France

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11618680/pdf/SNI-15-439.pdf

HUMAN-MACHINE FUSION (CYBORG)

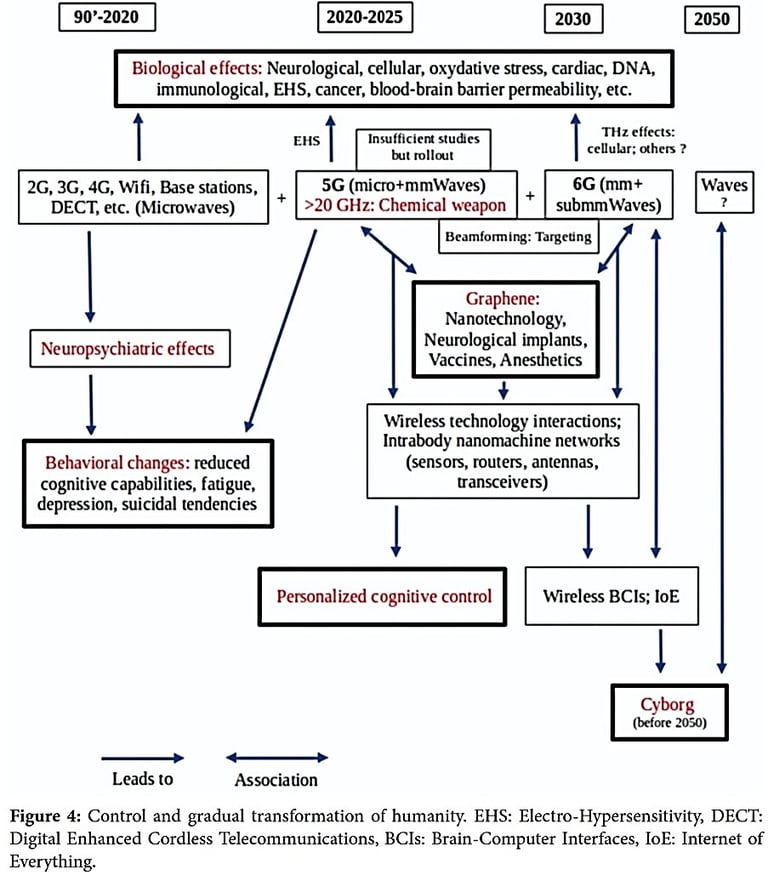

Scientific publications and military documents clearly show that the goal for the coming years is human-machine fusion.

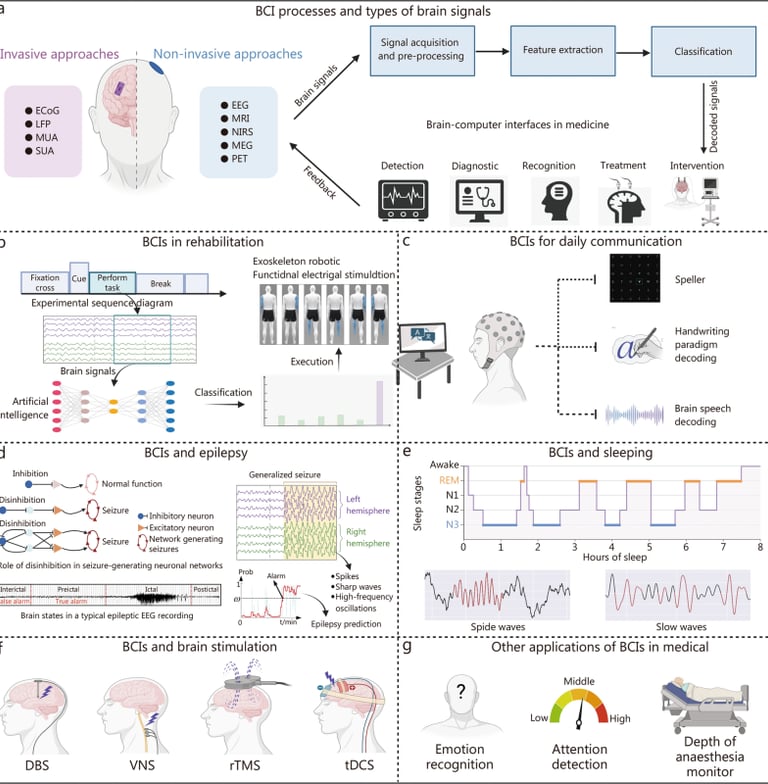

Medicine will first employ graphene brain implants.[21] Carbon nanomaterials can be connected to implantable brain-computer interfaces (BCIs),[89] and graphene nanosensors appear suitable for operating non-invasive BCIs.[48]

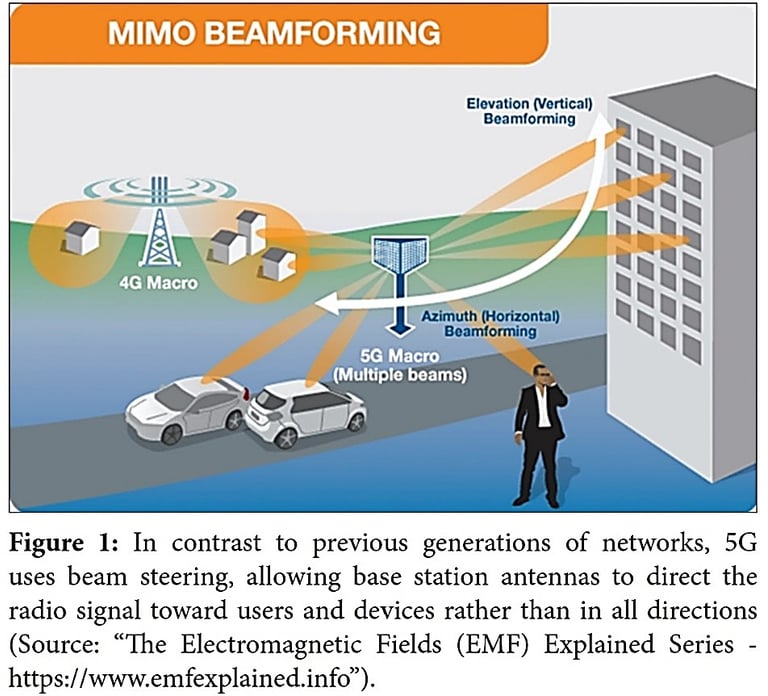

Via the vascular circulation, nanorobots (some carbon nanomaterials are being studied) could cross the BBB and attach themselves to the axons of neurons in the brain, which could then connect to the internet cloud through a BCI.[101] It should be noted that optimizing a BCI seems to require the intervention of artificial intelligence (AI) to study brain functions, but also to identify and monitor the neurons that control behavior.[139] e huge volumes of data exchanged between the cloud and the human brain will require AI to manage these interactions, too.[101] 6G network applications (2030) will enable wireless brain-computer interaction.[31] While 5G will enable wireless communication between simple physical objects (IoT), 6G, in which AI will play a key role, will bring networked communication of humans, processes, files, and objects (Internet of Everything (IoE)), such as people-to-machine and people-to-people connections via the internet.[13,75]

WEAPONIZATION OF NEUROLOGY

Cyborg by 2050

Weaponization of Technology

Race To Weaponise The Mind: How Brain Weapons Alter Memory & Behaviour

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ns9c1vD-hDE

The Battle For Your Brain Begins, Experts Warn: Your Thoughts Are At Risk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8UzY5qxw6Y

The Next Biotech War: AI + BCI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8UzY5qxw6Y

What technologies are already or will be weaponized?

FBI - Atlanta Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) FBI,

Federal Bureau of Investigation, National Security Agency (NSA), Defense Intelligence Agency, (DIA) U.S. Mission to NATO (US NATO), U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), U.S. Department of State (DOS)

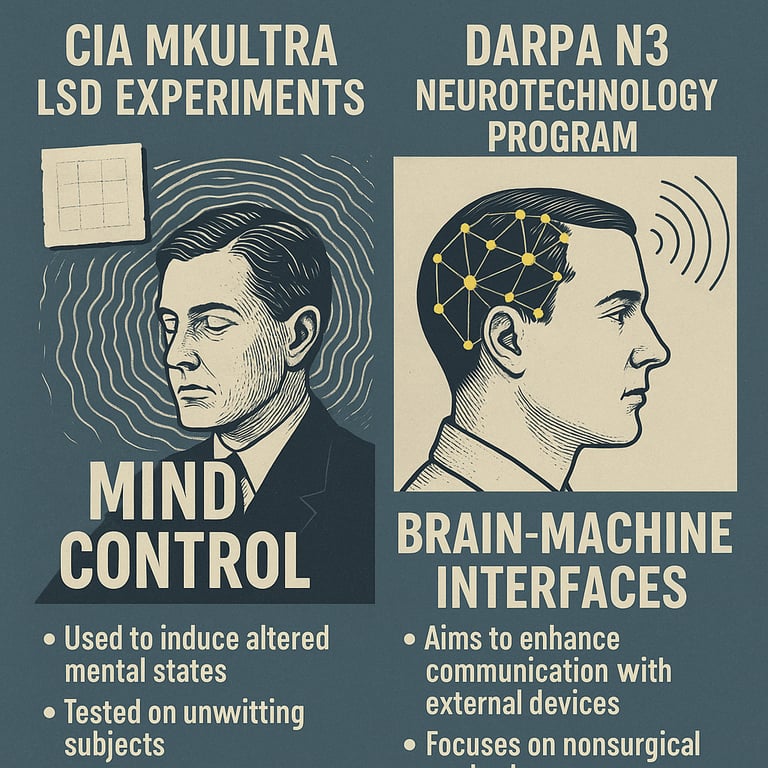

N3: Next-Generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology

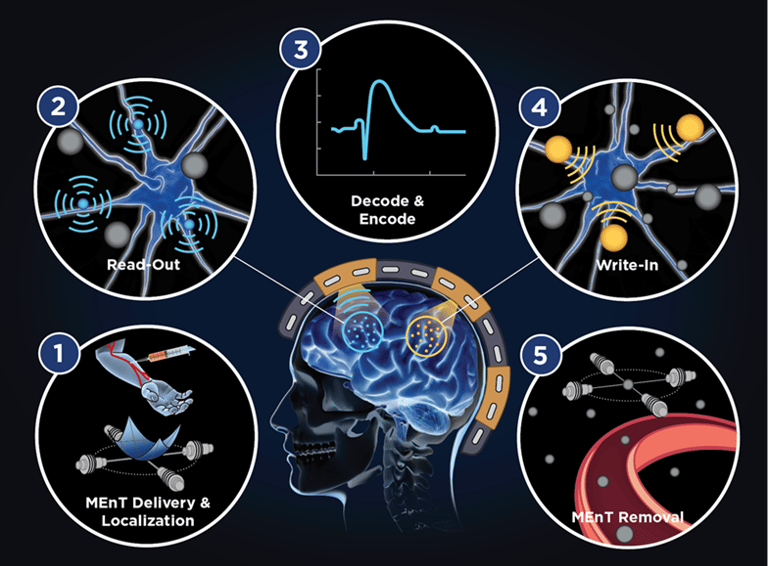

The Next-Generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology (N3) program aims to develop high-performance, bi-directional brain-machine interfaces for able-bodied service members.

Such interfaces would be enabling technology for diverse national security applications such as control of unmanned aerial vehicles and active cyber defense systems or teaming with computer systems to successfully multitask during complex military missions.

Whereas the most effective, state-of-the-art neural interfaces require surgery to implant electrodes into the brain, N3 technology would not require surgery and would be man-portable, thus making the technology accessible to a far wider population of potential users. Noninvasive neurotechnologies such as the electroencephalogram and transcranial direct current stimulation already exist, but do not offer the precision, signal resolution, and portability required for advanced applications by people working in real-world settings.

The envisioned N3 technology breaks through the limitations of existing technology by delivering an integrated device that does not require surgical implantation, but has the precision to read from and write to 16 independent channels within a 16mm3 volume of neural tissue within 50ms. Each channel is capable of specifically interacting with sub-millimeter regions of the brain with a spatial and temporal specificity that rivals existing invasive approaches. Individual devices can be combined to provide the ability to interface to multiple points in the brain at once.

To enable future non-invasive brain-machine interfaces, N3 researchers are working to develop solutions that address challenges such as the physics of scattering and weakening of signals as they pass through skin, skull, and brain tissue, as well as designing algorithms for decoding and encoding neural signals that are represented by other modalities such as light, acoustic, or electro-magnetic energy.

https://www.darpa.mil/research/programs/next-generation-nonsurgical-neurotechnology

DARPA’s N3: The Future of Non-Surgical Brain Interfaces

Oct 30, 2024

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)’s Next-Generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology (N3) project is an ambitious initiative aiming to develop vast array of nanoscalar sensing and transmitting brain-computational interfaces (BCIs). An axiomatic attribute of such a system is obviating the burden and risks of neurosurgical implantation by instead introducing the nanomaterials via intranasally, intravenously and/or intraorally, and using electromagnetic fields to migrate the units to their distribution within the brain. It’s said that location is everything, and so too here. Arrays would require precise placement in order to engage specific nodes and networks, and it’s unknown if -and to what extent any “drift” might incur in system fidelity.

The system works much like WiFi in that it’s all about parsing signal from the “noise floor” of the brain; but “can you hear me now?” takes on deeper implications when the sensing and transmitting dynamics involve “reading from” and “writing into” brain processes of cognition, emotions and behavior. I’d be the first one to argue for an “always faithful” paradigm of sensing and transmitting integrity; yet, even if the system and its workings are true to design, there’s still a possibility of components (and functions) being “hacked”. As work with Dr Diane DiEuliis has advocated, the need for “biocybersecurity-by-design” is paramount (not just for N3, but for all neurotech, given its essential reliance upon data).

By intent, N3 holds promise in medicine; but the tech is also provocative for communications (of all sorts), and its dual-use is obvious. Yes, Pandora, this jar’s been opened. If we consider the sum-totaled operations of the embodied brain to be “mind”, and N3-type tech is aimed at remotely sensing and modulating these operations, then it doesn’t require much of a stretch to recognize that this is fundamentally “mind reading” and “mind control”, at least at a basic level. And that’s contentious. In full transparency, I served as a consulting ethicist on initial stages of N3, and the issues spawned by this project were evident, and deeply discussed. But discussion is not resolution, and the “goods” as well as the gremlins and goblins of N3 tech have been loosed into the real world. The real world is multinational, and DARPA – and the US – are not alone in pursuing these projects. Nations’ and peoples’ values, needs, desires, economics, allegiances, and ethics differ, and any genuine ethical discourses – and policy governances – must account for that. The need for a reality check is now; the question is whether there is enough rational capital in regulatory institutions’ accounts to cash the check without bouncing bankable benefits into the realms of burdens, risks and harms. https://biodefenseresearch.org/darpas-n3-the-future-of-non-surgical-brain-interfaces/

Battelle Neuro Team Advances to Phase II of DARPA N3 Program

COLUMBUS, Ohio (Dec. 15, 2020)—A Battelle team of researchers has received funding to continue work on the second of a three-phase Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) program called Next-Generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology (N3).

The program is designed for teams around the country to develop a high-performance, bi-directional brain-computer interface (BCI) for noninvasive clinical applications or for use by able-bodied members of the military. Such neural interfaces would provide the enabling technology for diverse medical and national security applications and could enable enhanced multitasking during complex military missions.

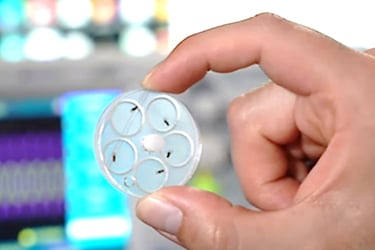

Battelle and its project partners from Cellular Nanomed Inc., the University of Miami, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Air Force Research Laboratory are working on an interface called BrainSTORMS (Brain System to Transmit Or Receive Magnetoelectric Signals). It employs magnetoelectric nanotransducers (MEnTs) localized in neural tissue for BCI applications. One of the key MEnT attributes are their incredibly small size—thousands of MEnTs can fit across the width of a human hair. The MEnTs are first injected into the circulatory system and then guided with a magnet to the targeted area of the brain. “Our current data suggests that we can non-surgically introduce MEnTs into the brain for subsequent bi-directional neural interfacing,” said Patrick Ganzer, a Battelle researcher and the principal investigator on the project.

Several technology development goals and N3 program metrics were achieved during Phase 1, such as precise reading and writing to neurons using this breakthrough technology, leveraging the multi-modal expertise of the BrainSTORMS team across the domains of electromagnetics, nanoscale materials, and neurophysiology.

“We are committed to achieving the Phase 2 metrics of the DARPA N3 program, building on the ground-breaking results we achieved in Phase 1 of the BrainSTORMS project,” said Ping Liang, the lead researcher at Cellular Nanomed Inc responsible for developing and building the electronics, power and control systems that interact with the MEnTs to achieve the BCI functions.

Phase 2 efforts will focus on maturing the capability sets of the MEnTs for writing information to the brain and advancing the construction and testing of the external writing interface.

“In Phase I, we demonstrated the main physics of MEnTs, i.e., two-way conversion of magnetic-to-electric field energy to control contactless activation of neurons. In Phase II, we will develop a next generation of MEnTs to achieve faultless multi-channel performance,” said Sakhrat Khizroev, Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Miami, in charge of the MEnTs’ synthesis.

If work progresses to the third phase, the Battelle team would implement a regulatory strategy developed with the FDA in phase two in order to support future human subjects testing.

About Battelle. Headquartered in Columbus, Ohio since its founding in 1929, Battelle serves the national security, health and life sciences, and energy and environmental industries. For more information, visit www.battelle.org.

Unlocking The Future: Controlling Drones With Your Mind - Darpa N3

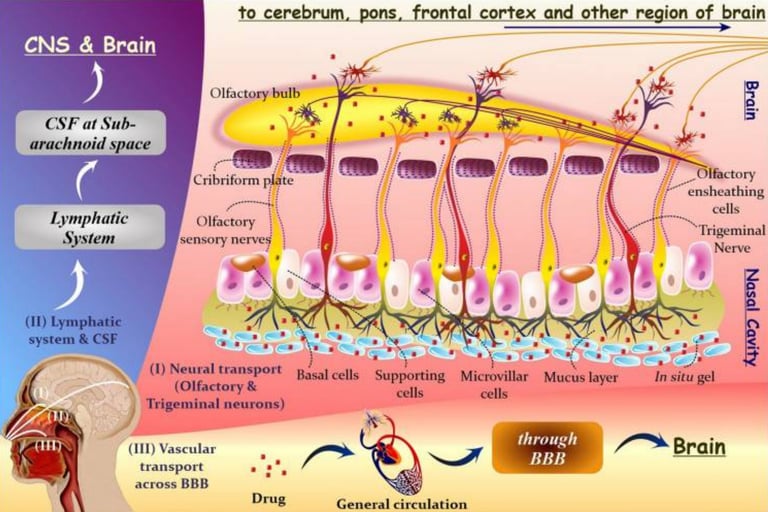

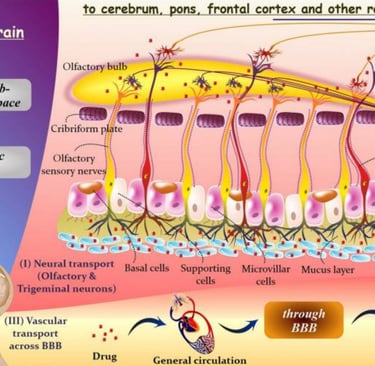

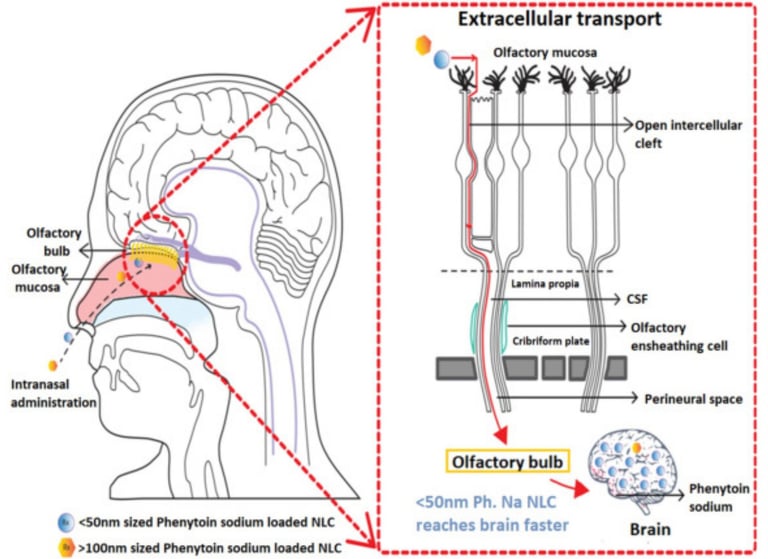

Intranasal mechanism of nose-to-brain delivery. The therapeutics can be transported from the nose to the brain through (I) neural transport through the olfactory and trigeminal nerves, (II) lymphatic system and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and (III) vascular transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The primary routes for nose-to-brain are olfactory and trigeminal nerve pathways. In contrast, the latter two serve as secondary passages. Reprinted from J Cont Rel, Volume 327, Agrawal M, Saraf S, Saraf S, et al. Stimuli-responsive in situ gelling system for nose-to-brain drug delivery. 235–265. Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10898487/

Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery Systems

Conventional methods of administering drugs for brain-targeting systems, such as oral and parenteral routes, involve delivering drugs into the brain through the systemic circulation. However, the majority of administered drugs often remain in the systemic circulation due to challenges in penetrating physiological barriers, such as the BBB. Specifically, large molecules and more than 98% of low-molecular-weight drugs face difficulties permeating the BBB, resulting in low brain bioavailability. Additionally, oral administration leads to hepatic first-pass metabolism and intestinal enzymatic degradation prior to the arrival of the drug in the brain. Parenteral administration, like intrathecal delivery, can lead to complications, such as cerebrospinal fluid leakage and meningeal issues. On the other hand, the receptor-mediated approach has gained attention as a potentially safe and effective method for enhancing brain-targeting capability without disrupting the BBB membrane. However, this strategy carries the risk of losing therapeutic effectiveness due to the accumulation of drug carriers in unintended sites, such as the liver.

For DARPA's N3 (Next-Generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology) program, Battelle Memorial Institute led by Dr. Gaurav Sharma developed the "BrainSTORMS" (Brain System to Transmit Or Receive Magnetoelectric Signals) technology, using injectable magnetoelectric nanoparticles to read and write neural activity, with other teams from Carnegie Mellon, Johns Hopkins APL, PARC, Rice, and Teledyne also developing different approaches, but Battelle's minutely invasive method was a key path to be matured.

Key Details:

Lead Organization: Battelle Memorial Institute.

Method Name: BrainSTORMS (Brain System to Transmit Or Receive Magnetoelectric Signals).

Technology: A minutely invasive system using injectable nanoparticles and an external transceiver to interact with neurons.

Goal: To create high-bandwidth, bidirectional brain-computer interfaces without major surgery, benefiting both defense and clinical needs.

Other Teams in N3:

Carnegie Mellon University: Noninvasive acousto-optical approach.

Johns Hopkins APL: Noninvasive optical system.

PARC (Palo Alto Research Center): Noninvasive acousto-magnetic device.

Rice University: Minutely invasive, bidirectional system using viral vectors.

Teledyne Scientific: Noninvasive system using optically pumped magnetometers and focused ultrasound.

In 1989, William H. Frey II introduced intranasal administration as a non-invasive approach for nose-to-brain delivery. This approach capitalizes on the direct connection between the olfactory nerve and the frontal region of the brain, facilitated by the olfactory bulb, as well as the entry of the trigeminal nerve through the trigeminal ganglion and pons. These connections provide opportunities for bypassing the BBB, evading hepatic first-pass effects, and preventing intestinal enzyme degradation. Nose-to-brain delivery also boasts high patient compliance and affordability, and it eliminates the need for expert interventions. General information regarding oral, parenteral, and intranasal administration routes is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1 outlines the original Phase 1 approach, in which MEnTs are first injected into the circulatory system, localized into the cerebral tissue using a magnetic field gradient, and then interact with neural tissue and applied magnetic fields to provide non-surgical neural interfacing.

n the BrainSTORMS approach, however, the nanotransducer could be temporarily introduced into the body via injection and then directed to a specific area of the brain to help complete a task through communication with a helmet-based transceiver. Upon completion, the nanotransducer could be magnetically guided out of the brain and into the bloodstream to be processed out of the body.

The nanotransducer would use magnetoelectric nanoparticles to establish a bi-directional communication channel with the brain. Neurons in the brain operate through electrical signals. The magnetic core of the nanotransducers would convert the neural electrical signals into magnetic ones that would be sent through the skull to the helmet-based transceiver worn by the user. The helmet transceiver could also send magnetic signals back to the nanotransducers where they would be converted to electrical impulses capable of being processed by the neurons, enabling two-way communication to and from the brain.

MOANA (Magnetic, Optical, and Acoustic Neural Access) led by Rice University

The Moana project, led by a team at Rice University team under principal investigator Dr. Jacob Robinson, aims to develop a minutely invasive, bidirectional system for recording from and writing to the brain. For the recording function, the interface will use diffuse optical tomography to infer neural activity by measuring light scattering in neural tissue. To enable the write function, the team will use a magneto-genetic approach to make neurons sensitive to magnetic fields.

“The custom power electronics developed by our collaborators Angel Peterchev and Stefan Goetz at Duke University allow us to slightly raise the temperature of specific nanoparticles that can be injected into an animal model,” explains Robinson, associate professor ECE and BioE at Rice. “When heated, these nanoparticles made by Gang Bao’s lab at Rice can activate select genetically modified insect brain cells. Using different amplitude and field strength of magnetic fields we’ve shown that we can quickly turn on and off specific behaviors in fruit flies using a remotely applied magnetic field. In the future, and in conjunction with the US FDA, we hope to use similar technologies to remotely activate specific neurons in the visual cortex of humans to help restore sight to people that suffer from blindness.”

The objective is to design to provide a high-bandwidth brain-computer-interface without the need for a surgically implanted device. The device will consist of an array of flexible complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) chiplets that can conform to the surface of the scalp and implement our optical readout technology based on Time-of-Flight Functional Diffuse Optical Tomography (ToFF-DOT).

In the early Cold War era, the CIA launched Project MKULTRA (1953) amid fears that adversaries might have gained “mind control” techniques. The goal was to develop methods to control or break an individual’s will for intelligence purposes nsarchive.gwu.edu. Under MKULTRA (and predecessor programs codenamed BLUEBIRD and ARTICHOKE), the Agency explored hypnosis, sensory deprivation, and especially drugs as tools for interrogation and brainwashing. Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) — a powerful psychedelic — quickly became central to these experiments nsarchive.gwu.edunsarchive.gwu.edu. CIA officials like Dr. Sidney Gottlieb (head of the CIA’s Technical Services) believed LSD might be a “truth drug” or mind control substance that could render subjects compliant or extract secrets nsarchive.gwu.edunsarchive.gwu.edu. There was also a defensive motive: understanding LSD’s effects in case U.S. personnel were drugged by enemies intelligence.senate.govintelligence.senate.gov. In short, the CIA hoped LSD could alter consciousness in a way that gave them control over minds — or at least help break down a person’s resistance during interrogation nsarchive.gwu.edu.

The rapid advancement of neuroscience and its corresponding technologies has prompted renewed and growing interest in both its development and the ethical concerns about the use of such techniques and tools in military and security contexts.

In 2008, the National Research Council of the National Academies of Science reported that the brain sciences showed potential for military and warfare applications, but were not yet wholly viable for operational use. However, by 2014, a subsequent report of the National Academies, “Emerging and Readily Available Technologies and National Security: A Framework for Addressing Ethical, Legal and Societal Issues,” concurred with a series of white papers by the strategic multilayer assessment group of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and a 2013 Nuffield Council Report, stating that developments in the field had progressed to the extent that rendered the brain sciences viable, of definitive value and a realistic concern for the military.

This timeline is important, as it reflects the rapid and iteratively more sophisticated capability to create and exploit neuroscientific methods and technologies to access the brain, and assess and affect its functions of cognition, emotion and behavior.

Advancements in neuroscience could be used to create “super soldiers,” link brains to weapon systems for command and control, or even manipulate groups or leaders into taking actions that they normally wouldn’t do.

Obviously, new developments in brain science can be harnessed to improve neurological and psychiatric care within military medicine, and a number of ongoing Defense Department programs are doing so. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Army Medical Research and Materiel Command and the Naval Bureau of Medicine and Surgery are generating new techniques and technologies for treating brain injury, neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, and certain psychiatric conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

However, there is also considerable potential for dual-use applications of neuroscientific methods and tools that extend beyond the bedside. Many of these may reach battlefields.

These include the use of various drugs and forms of neurotechnologies such as neurofeedback, transcranial electrical and magnetic stimulation, and perhaps even implantable devices for training and performance optimization of intelligence and combat personnel. Brain-computer interfaces could be used to control aircraft, boats or unmanned vehicles. Military and warfare uses also entail the development and engagement of agents — such as drugs, microbes, toxins — and “devices as weapons,” also called neuroweapons, to affect the nervous system and modify opponents’ thoughts, feelings, senses, actions, health or — in some cases — to incur lethal consequences.

The use of neuroscience and technology to optimize the performance of military personnel could potentially lead to the creation of “super soldiers.” This remains a provocative and contentious issue.

When viewed in a positive light, such approaches could — and arguably should — be employed to prevent warfare. For example, intelligence and military personnel who have increased cognitive, emotional and/or behavioral capacities might be able to more easily and capably detect threats, function under arduous conditions with less stress, and have increased sensitivity to socio-cultural and physical cues and nuances in foreign environments. They could be more effective in reducing the risk of violence.

These goals led to efforts such as the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity’s Sociocultural Content in Language program and the Metaphor program, which both sought to improve insight into cultural linguistic and emotional norms. DARPA’s Narrative Networks program aimed to utilize neurocognitive science and technology to improve narratives in socio-cultural contexts.

On the other hand, there are concerns for the negative effects that the field might have on “neuro-modified” individuals’ health. There is trepidation about using such approaches to turn warfighters into amoral, combative automatons and questions about what responsibilities and burdens might be incurred for — and borne by — the military, and perhaps society at large, when dealing with such effects.

But while such questions and concerns may suggest the need for a reflective pause, it’s important to note that brain research and its corresponding technologies are becoming ever more international, and a number of countries such as China and Russia, and some U.S. allies, are engaged in these pursuits and are interested in their military viability and use. This creates a situation that tends to sustain, if not advance the pace and extent of research, development and incorporation of neuroscience and technology in intelligence and military initiatives.

The internationalization of brain science, taken together with the speed of its progress, fosters additional concerns about the development and use of neuroweapons.

While existing international agreements on biological and chemical weapons such as the Hague Conventions, Geneva Protocol and the Biologic, Toxin and Weapons Convention limit institutional research, stockpiling and international trade of certain toxins and neuro-microbiologicals such as ricin and anthrax, some neurobiological substances and technologies developed for medical products that are readily available on the commercial market might not fall within existing international rules.

These include neurotropic drugs created in pharmaceutical labs, bio-regulators — defined as substances that affect biological processes, such as opioids and other peptides — and neuromodulatory technologies such as transcranial or deep brain stimulating devices.

And, as noted in the 2008 National Academy of Sciences report, products intended for the health market can — and frequently are — studied and developed for possible employment in military applications. In the United States, any such activity in federally funded programs would be subject to oversight in accordance with dual-use policies, reflecting the general tenor of current international biological and chemical weapons conventions.

The increasing availability of tools for DIY neurobiology, such as gene-editing kits that can be employed to genetically modify existing microbes and toxins and make them more potent or lethal, increases the probability of both their use, and attendant risks and threats that such techniques and their products pose to national security. Former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper stated last year that gene editing should be regarded for its potential for creating biological weapons. [Morgellons has already been put in many Targeted Individuals]

The impact of neuroweapons is equally important to consider. While nerve agents such as sarin, or pathogens such as anthrax, can induce somewhat widespread effects, other, more sophisticated neuroweapons should not be regarded as weapons of mass destruction, but rather as “weapons of mass disruption,” often with subtle, albeit intensifying effects.

For instance, neurologically acting drugs can be used to selectively target the thoughts, sentiments and actions of an individual, such as a political or military leader, to evoke a change in his or her ideas, emotions and behavior. This could exert effect on those they lead, influencing their views and actions toward either conformity or dissonance.

Certain neuroactive drugs, toxins and/or microbes can also be used against larger scale targets to incur “ripple consequences” within a group, community or population. For example, these agents could be dispersed to produce “sentinel cases” of individuals who exhibit neuro-psychiatric and other physical signs and symptoms. Attribution as a terrorist action, and accompanying misinformation about salient and escalating signs and symptoms — such as anxiety, sleeplessness and paranoia — could be propagated over the internet.

Brain science confers powerful capabilities to affect “minds and hearts” and therefore affords clear and present leverage in military and warfare operations.

Neuroweapons encompass biological agents, chemical weapons, and even directed energy targeted at the brains and central nervous systems of enemy combatants. According to some observers, neuroweapons have the potential to disrupt everything — from individual cells in a body to societies and geopolitics.[1]

Understandably, there are serious ethical concerns about the use of neuroweapons and what could happen if they got into the wrong hands. For example, in 2021, U.S. officials accused China of using emerging biotechnologies to try to develop “brain-control technologies” through military applications that included gene editing, human performance enhancement, and brain-machine interfaces.[4]

Even the U.S. Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Project,[5] launched in 2013, has gone in some questionable directions. The BRAIN Project was initially presented to the public as having the potential to produce research with vast beneficial health implications. However, much of the funding went through the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency — a military organization. When science and military are mixed through dual-use research, the priorities of the latter often dominate the trajectory of the former.[6] In 2013, the U.S. National Institutes of Health reported that the BRAIN Project was looking to develop electromagnetic modulation as a new technology for brain circuit manipulation, heralding a shift in research from drug research to brain circuit research. Specifically, the project intended to explore optogenetics, which involves injecting neurons with a benign virus that contains genetic information for light-sensitive proteins.[7] The brain cells then become light sensitive themselves, and their activity can be controlled with millisecond flashes of light sent through embedded fiber optic cables. This kind of research has alarming implications, and the development of these kinds of technologies should be heavily regulated.

To advance brain science and ensure neuroweapons of this type are not developed or used, it is essential that major players in the Americas, Asia, and Europe collaborate as they each have comparative advantages and have focused their research in a coordinated and coherent way in the past. The recently launched China Brain Project (CBP) could offer opportunities for international cooperation with researchers at the U.S. Brain Initiative and the EU Human Brain Project.[8] The CBP seeks to understand the neural basis of cognitive functions, diagnose and treat brain disorders, and conduct brain-inspired computing — research that could complement the work being done in the U.S. and EU.

Above all, it is crucial that brain science is used to improve brain health and is not used for harmful purposes. International treaties banning the development and use of neuroweapons should be strictly adhered to.

"Neuroweapons" weapons target or exploit brain functions and apply to both offensive capabilities (e.g., disrupting cognition or behavior) and defensive/enhancement applications (e.g., boosting soldiers' abilities). These technologies raise ethical, legal, and security concerns due to their dual-use nature — they can serve medical or beneficial purposes but they can also be weaponized.

Gene Editing (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9)--[MORGELLONS]

Gene editing tools like CRISPR can modify DNA to alter traits or functions. In neuroweapons discussions, they could theoretically create or enhance neurotropic agents (substances targeting the nervous system) by:

Boosting production of neurotoxins for greater potency or stability.

Engineering organisms or agents that affect brain function indirectly (e.g., via modified microbes or toxins).

This is largely speculative and focused on dual-use risks rather than confirmed deployment. For instance, CRISPR could accelerate development of novel neuroactive substances, though no public evidence exists of weaponized gene-edited neuroweapons.

Human Performance Enhancement

This involves technologies or methods to improve cognitive, emotional, or physical abilities beyond normal levels. In military contexts, it includes:

Pharmaceutical nootropics or stimulants for focus and endurance.

Neural stimulation or implants to enhance decision-making or memory.

Augmented cognition via AI integration.

Enhancement could be framed as a neuroweapon if used to create "super-soldiers" or disrupt adversaries (e.g., by degrading performance). U.S. programs like DARPA's efforts explore these for national security, while concerns arise about coercion, inequality, or misuse.

Brain-Machine Interfaces (BMIs) / Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs)

These create direct links between the brain and external devices. Examples include:

Non-invasive (e.g., EEG headsets) or invasive (e.g., implants like Neuralink).

Allowing thought-controlled drones, prosthetics, or data processing.

In military applications, they could enable faster decision-making, hands-free control of systems, or team communication. However, they raise risks like hacking, data privacy breaches, or coercion.

Neuroscience JUST Did the IMPOSSIBLE

Neuroscience JUST Did the IMPOSSIBLE

Psilocybin triggers an activity-dependent rewiring of large-scale cortical networks

Psilocybin holds promise as a treatment for mental illnesses. One dose of psilocybin induces structural re-modeling of dendritic spines in the medial frontal cortex in mice. The dendritic spines would be innervated by presynaptic neurons, but the sources of these inputs have not been identified. Here, using monosynaptic rabies tracing, we map the brain-wide distribution of inputs to frontal cortical pyramidal neurons. We discover that psilocybin’s effect on connectivity is network specific, strengthening the routing of inputs from perceptual and medial regions (homolog of the default mode network) to subcortical targets while weakening inputs that are part of cortico-cortical recurrent loops. The pattern of synaptic reorganization depends on the drug-evoked spiking activity because silencing a presynaptic region during psilocybin administration disrupts the rewiring. Collectively, the results reveal the impact of psilocybin on the connectivity of large-scale cortical networks and demonstrate neural activity modulation as an approach to sculpt the psychedelic-evoked neural plasticity. https://www.cell.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0092-8674%2825%2901305-4

Join us in advocating against the misuse of technology.

contact@targetedhumans.org

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Targeted Humans Inc.